Dynamics: Mechanical principles

Following kinematics, dynamics comes into play, which involves the study of the forces and torques that cause the motion, bridging the gap between the motion observed and the reasons behind it. In this section, we shortly recap mechanical principles, which are used throughout for the simulation of multibody systems.

Newton’s basic principles

In the study of multibody systems, Newton’s basic principles lay the foundational framework. At the heart of these principles are three laws that govern the motion of bodies:

1. Newton’s first law (law of inertia): A body remains at rest, or in uniform motion in a straight line, unless acted upon by a force \({\mathbf{f}}\), expressed as:

where \({\mathbf{f}}\) is the net force applied to the body, and \(\frac{d{\mathbf{v}}}{dt}\) is the acceleration of the body.

2. Newton’s second law (law of motion): The sum of the forces F acting on a point mass equals the change in momentum of this mass,

where \({\mathbf{J}}\) is the (linear, translational) momentum of the mass \(m\). Assuming a constant mass of the body (which is not true for some cases such as rockets), we find that the acceleration \({\mathbf{a}}\) of an object is directly proportional to the net force \({\mathbf{f}}\) acting upon it and inversely proportional to its mass, given by the equation:

where \(m\) is the mass of the object.

3. Newton’s third law (action and reaction): For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction. This principle is fundamental in analyzing the interactions within multibody systems and can be summarized as:

in which we observe \({\mathbf{f}}_{12}\) as the force exerted by body 1 on body 2, and \({\mathbf{f}}_{21}\) as the force exerted by body 2 on body 1.

These principles are pivotal in understanding and modeling the dynamics of multibody systems, providing the basis for further exploration and analysis in this field.

Newton’s principles represent linear (translational) motion, but may be transformed to rotations by using angular momentum, as well. This leads to Euler’s equations, see the description of the ObjectRigidBody.

The Lagrange-d’Alembert principle

For a constant mass \(m\), it follows from Newton’s second law that

Eq. (5) can also be written in the form

The vector \((- m {\mathbf{a}} )\) is referred to as the inertia force, since it can apparently be balanced to zero in the sense of a generalized equilibrium. This equilibrium is called dynamic equilibrium, in analogy to statics.

In D’Alembert’s Principle, the inertia force \({\mathbf{f}}_i = -m {\mathbf{a}}\) is introduced, and the sum of the forces is written as

where applied forces \({\mathbf{f}}_e\) and constraint forces \({\mathbf{f}}_c\) are distinguished.

A key property of the constraint forces is that the virtual work done by constraint forces always vanishes,

where here \(\delta {\mathbf{r}}\) is the virtual displacement associated with the constraint force.

Generalized Principle of Virtual Work

With the generalized principle of virtual work, it follows

Thus, we obtain the Lagrange-d’Alembert principle as

with the virtual work \(W_e\) of applied forces and \(W_i\) of inertia forces,

For a system of \(n\) mass points, it follows

It is ultimately characterized by the fact that, in comparison to D’Alembert’s principle, constraint forces do not appear.

Note that this principle is used in Exudyn at many places to derive equations for rigid and flexible bodies, as well as for connectors, such as spring-dampers.

Virtual displacements

The virtual displacement \(\delta {\mathbf{r}}_j\) or the variation of any quantity can be written in terms of variation of the underlying coordinates, see Section Generalized coordinates,

Generalized Forces

To derive the Lagrangian equations, we first consider the virtual work done by \(N\) forces on \(N\) mass points

Here, \({\mathbf{f}}_j\) represents the force on, and \(\delta {\mathbf{r}}_j\) represents the displacement of, the \(j\)th mass point.

Using Eq. (7), the virtual work can be expressed as

In the process of translating the virtual work of forces or moments, we identify what are called generalized forces \(Q_i\),

Consequently, the virtual work can also be written as,

Lagrange’s Equations of Motion

We define the kinetic energy as \(T\), which for \(N\) mass points is given by

Using the kinetic energy \(T\), the following Lagrangian equations can be written,

These are valid under the assumption of minimal coordinates with holonomic constraints, resulting in the fact that all virtual displacements \(\delta q_i\) are independent of each other.

For forces that possess a potential \(V\), i.e. the variation of the potential reads

and assuming that \(Q_i\) now only includes forces without a potential, the Lagrange equations can be rewritten as follows,

With the definition \(L=T-V\) and the relationship \(\frac{\partial V}{\partial \dot q_i} = 0\), a common form of Lagrange’s equations is obtained:

This equation is also used sometimes to derive equations of motion for rigid or flexible bodies in Exudyn.

Multibody formulations: redundant and minimal coordinates

In multibody system dynamics, we primarily distinguish between two formulations:

redundant coordinates

minimal coordinates

Formulations based on minimal coordinates appeared naturally and early, in principle every model in dynamics, such as a 1D motion of a mass point according to Newton’s laws, see Eq. (4), Euler’s equations, or a single DOF mass-spring-damper model. The advantages of a minimal-coordinates formulation are:

coordinates represent the degrees of freedom

direct access to relevant coordinates

direct application of forces to the coordinates

application of any class of solvers, as long as equations are non-stiff

The disadvantages are related to the additional efforts to derive the equations of motion, which has to be done for every different system, and the general restriction to open-loop systems, making it difficult to be applied to closed-loop systems (but not always impossible). There are many modifications, which allow closed-loop systems, e.g., via augmented Lagrangians or similar approaches.

A redundant-coordinates formulation has the following advantages:

being extremely versatile and allowing practically any combination of (closed-loop) constraints

easy extension to flexible bodies, sliding constraints, etc.

multibody systems can be created easily by combining a set of bodies and constraints (\(\ra\) user friendly)

Disadvantages are clearly the resulting index 3 (position-level) constraints, for which only very few implicit solvers (time integration) exist, and it requires always matrix factorization during solving. A further problem is that this formulation may potentially lead to redundant constraints, which need to be treated specially with solvers, and that the degrees of freedom are less obvious and that relevant (e.g., joint) coordinates are not directly accessible on the equations level.

It is left to the user, which formulation to chose when working with multibody systems.

In Exudyn, there is the option to create tree-like rigid body systems

using the ObjectKinematicTree, which allows to use minimal coordinates for open-loop systems. In general, Exudyn is a redundant

multibody dynamics formulation for reasons of simpler assembly of equations of motion.

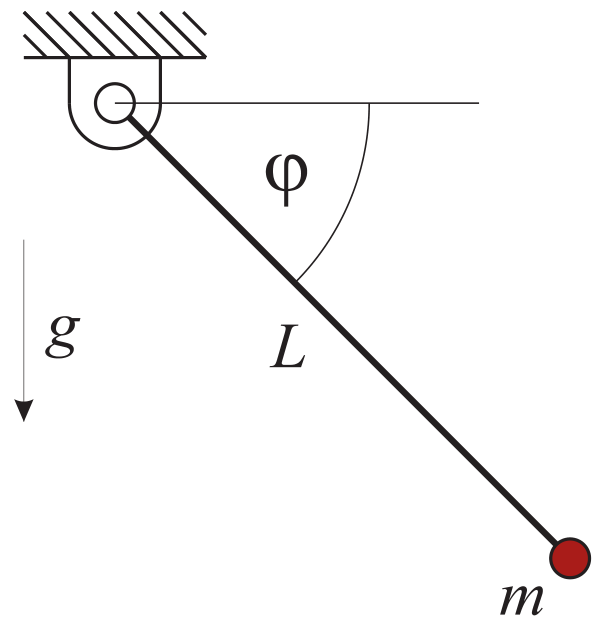

As an example, we investigate the equations of motion for a mathematical pendulum with mass \(m\), distance \(L\) between support and mass, under gravity \(g\).

In the minimal coordinates formulation, see Fig. 17, we define the angle \(\varphi\), being zero in the horizontal configuration,

leading to one \(2^\mathrm{nd}\) order ordinary differential equation (ODE2), using the minimal coordinate \(\varphi\).

Fig. 17 Mathematical pendulum with minimal coordinate \(\varphi\).

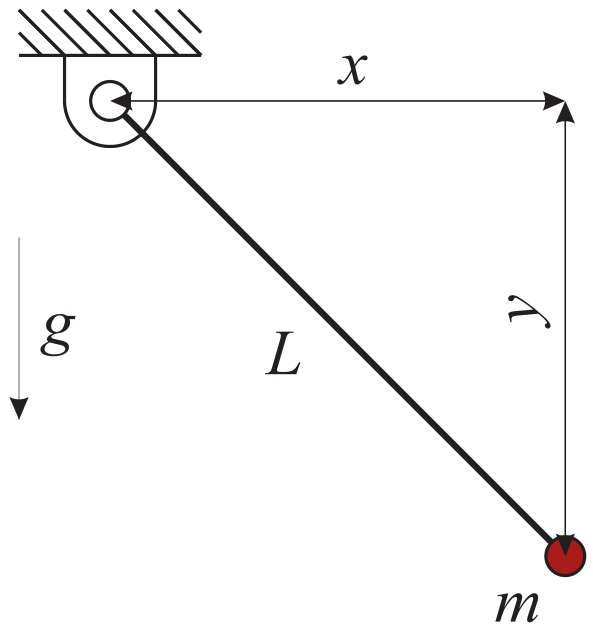

With redundant coordinates, see Fig. 18, we may introduce two Cartesian coordinates (\(x\), \(y\)), to define the location of the mass in the plane, leading to two differential equations for the mass point,

together with a constraint equation

Fig. 18 Mathematical pendulum with redundant coordinates (\(x\), \(y\)).

Note that Eq. (9) and Eq. (10) include 3 equations for only two unknowns (\(x\), \(y\)). Therefore, we need to introduce an additional unknown Lagrange multiplier \(\lambda\) for the redundant multibody formulation, which represents a force in direction of the pendulum’s string, exactly such that the length \(L\) is preserved. The factor \(\lambda\) has to be projected with the constraint derivatives (Jacobian) onto the coordinates (\(x\), \(y\)), giving the forces

Therefore, we can rewrite Eq. (9) as

with the algebraic constraint, written in a computationally more efficient form,

The equations of motion are formed by both Eq. (11) and Eq. (12), which are differential-algebraic equations (DAEs) of index 3 and therefore much harder to solve than ordinary differential equations in case of minimal coordinates.

In Exudyn, we therefore use either the generalized-\(\alpha\) solver, or an implicit trapezoidal rule in combination with an index 2 reduction, see the section on solvers for more details.