Exudyn Basics

This section will show:

Interaction with the Exudyn module

Simulation settings

Visualization settings

Generating output and results

Graphics pipeline

Generating animations

Interaction with the Exudyn module

It is important that the Exudyn module is basically a state machine, where you create items on the C++ side using the Python interface. This helps you to easily set up models using many other Python modules (numpy, sympy, matplotlib, …) while the computation will be performed in the end on the C++ side in a very efficient manner.

Where do objects live?

Whenever a system container is created with SC = exu.SystemContainer(), the structure SC becomes a variable in the Python interpreter, but it is managed inside the C++ code and it can be modified via the Python interface.

Usually, the system container will hold at least one system, usually called mbs.

Commands such as mbs.AddNode(...) add objects to the system mbs.

The system will be prepared for simulation by mbs.Assemble() and can be solved (e.g., using exu.SolveDynamic(...)) and evaluated hereafter using the results files.

Using mbs.Reset() will clear the system and allows to set up a new system. Items can be modified (ModifyObject(...)) after first initialization, even during simulation.

Simulation settings

The simulation settings consists of a couple of substructures, e.g., for solutionSettings, staticSolver, timeIntegration as well as a couple of general options – for details see Section SolutionSettings and Section Simulation settings.

Simulation settings are needed for every solver. They contain solver-specific parameters (e.g., the way how load steps are applied), information on how solution files are written, and very specific control parameters, e.g., for the Newton solver.

The simulation settings structure is created with

simulationSettings = exu.SimulationSettings()

Hereafter, values of the structure can be modified, e.g.,

tEnd = 10 #10 seconds of simulation time:

h = 0.01 #step size (gives 1000 steps)

simulationSettings.timeIntegration.endTime = tEnd

#steps for time integration must be integer:

simulationSettings.timeIntegration.numberOfSteps = int(tEnd/h)

#assigns a new tolerance for Newton's method:

simulationSettings.timeIntegration.newton.relativeTolerance = 1e-9

#write some output while the solver is active (SLOWER):

simulationSettings.timeIntegration.verboseMode = 2

#write solution every 0.1 seconds:

simulationSettings.solutionSettings.solutionWritePeriod = 0.1

#use sparse matrix storage and solver (package Eigen):

simulationSettings.linearSolverType = exu.LinearSolverType.EigenSparse

Generating output and results

The solvers provide a number of options in solutionSettings to generate a solution file. As a default, exporting the solution of all system coordinates (on position, velocity, … level) to the solution file is activated with a writing period of 0.01 seconds.

Typical output settings are:

#create a new simulationSettings structure:

simulationSettings = exu.SimulationSettings()

#activate writing to solution file:

simulationSettings.solutionSettings.writeSolutionToFile = True

#write results every 1ms:

simulationSettings.solutionSettings.solutionWritePeriod = 0.001

#assign new filename to solution file

simulationSettings.solutionSettings.coordinatesSolutionFileName= "myOutput.txt"

#do not export certain coordinates:

simulationSettings.solutionSettings.exportDataCoordinates = False

Furthermore, you can use sensors to record particular information, e.g., the displacement of a body’s local

position, forces or joint data. For viewing sensor results, use the PlotSensor function of the

exudyn.plot tool, see the rigid body and joints tutorial.

Finally, the render window allows to show traces (trajectories) of position sensors, sensor vector quantities (e.g., velocity vectors),

or triads given by rotation matrices. For further information, see the sensors.traces structure of VisualizationSettings, Section VSettingsTraces.

Renderer and 3D graphics

A 3D renderer is attached to the simulation. Visualization is started with SC.renderer.Start(), see the examples and tutorials.

In order to show your model in the render window, you have to provide 3D graphics data to the bodies. Flexible bodies (e.g., FFRF-like) can visualize their meshes. Further items (nodes, markers, …) can be visualized with default settings, however, often you have to turn on drawing or enlarge default sizes to make items visible. Item number can also be shown.

Finally, since version 1.6.188, sensor traces (trajectories) can be shown in the render window, see the VisualizationSettings in Section Visualization settings.

The renderer uses an OpenGL window of a library called GLFW, which is platform-independent. The renderer is set up in a minimalistic way, just to ensure that you can check that the modeling is correct.

Note:

For closing the render window, press key ‘Q’ or Escape or just close the window.

There is no way to contruct models inside the renderer (no ‘GUI’).

Try to avoid huge number of triangles in STL files or by creating large number of complex objects, such as spheres or cylinders.

After

visualizationSettings.window.reallyQuitTimeLimitseconds a ‘do you really want to quit’ dialog opens for safety on pressing ‘Q’; if no tkinter is available, you just have to press ‘Q’ twice. For closing the window, you need to click a second time on the close button of the window afterreallyQuitTimeLimitseconds (usually 900 seconds).

Here are the main features of the renderer, using keyboard and mouse, for details see Section Graphics and visualization:

press key H to show help in renderer

move model by pressing left mouse button and drag

rotate model by pressing right mouse button and drag

for further mouse functionality, see Section Mouse input

change visibility (wire frame, solid, transparent, …) by pressing T

zoom all: key A

open visualization dialog: key V, see Section Visualization settings dialog

open Python command dialog: key X, see Section Execute Command and Help

show item number: click on graphics element with left mouse button

show item dictionary: click on graphics element with right mouse button

for further keys, see Section Keyboard input or press H in renderer

raytracing mode, see Section Raytracing

Depending on your model (size, place, …), you may need to adjust the following general visualization and openGL parameters in visualizationSettings, see Section Visualization settings:

change window size

light and light position; switch

openGL.lightPositionsInCameraFrameto switch between model-fixed or camera-fixed lightsshadow (turned off by using shadow=0; turned on by using, e.g., a value of 0.3) and shadow polygon offset; shadow slows down graphics performance by a factor of 2-3, depending on your graphics card

visibility of nodes, markers, etc. in according bodies, nodes, markers, …,

visualizationSettingsmove camera with a selected marker: adjust

trackMarkerinvisualizationSettings.interactive

NOTE: changing visualizationSettings is not thread-safe, as it allows direct access to the C++ variables.

In most cases, this is not problematic, e.g., turning on/off some view parameters my just lead to some short-time artifacts if

they are changed during redraw. However, more advanced quantities (e.g., trackMarker or changing strings) may lead to problems,

which is why it is strongly recommended to:

set all

visualizationSettingsbefore start of renderer

Visualization settings dialog

Visualization settings are used for user interaction with the model. E.g., the nodes, markers, loads, etc., can be visualized for every model. There are default values, e.g., for the size of nodes, which may be inappropriate for your model. Therefore, you can adjust those parameters. In some cases, huge models require simpler graphics representation, in order not to slow down performance – e.g., the number of faces to represent a cylinder should be small if there are 10000s of cylinders drawn. Even computation performance can be slowed down, if visualization takes lots of CPU power. However, visualization is performed in a separate thread, which usually does not influence the computation exhaustively.

Details on visualization settings and its substructures are provided in Section Visualization settings. These settings may also be edited by pressing ‘V’ in the active render window (does not work, if there is no active render loop using, e.g., SC.renderer.DoIdleTasks() ).

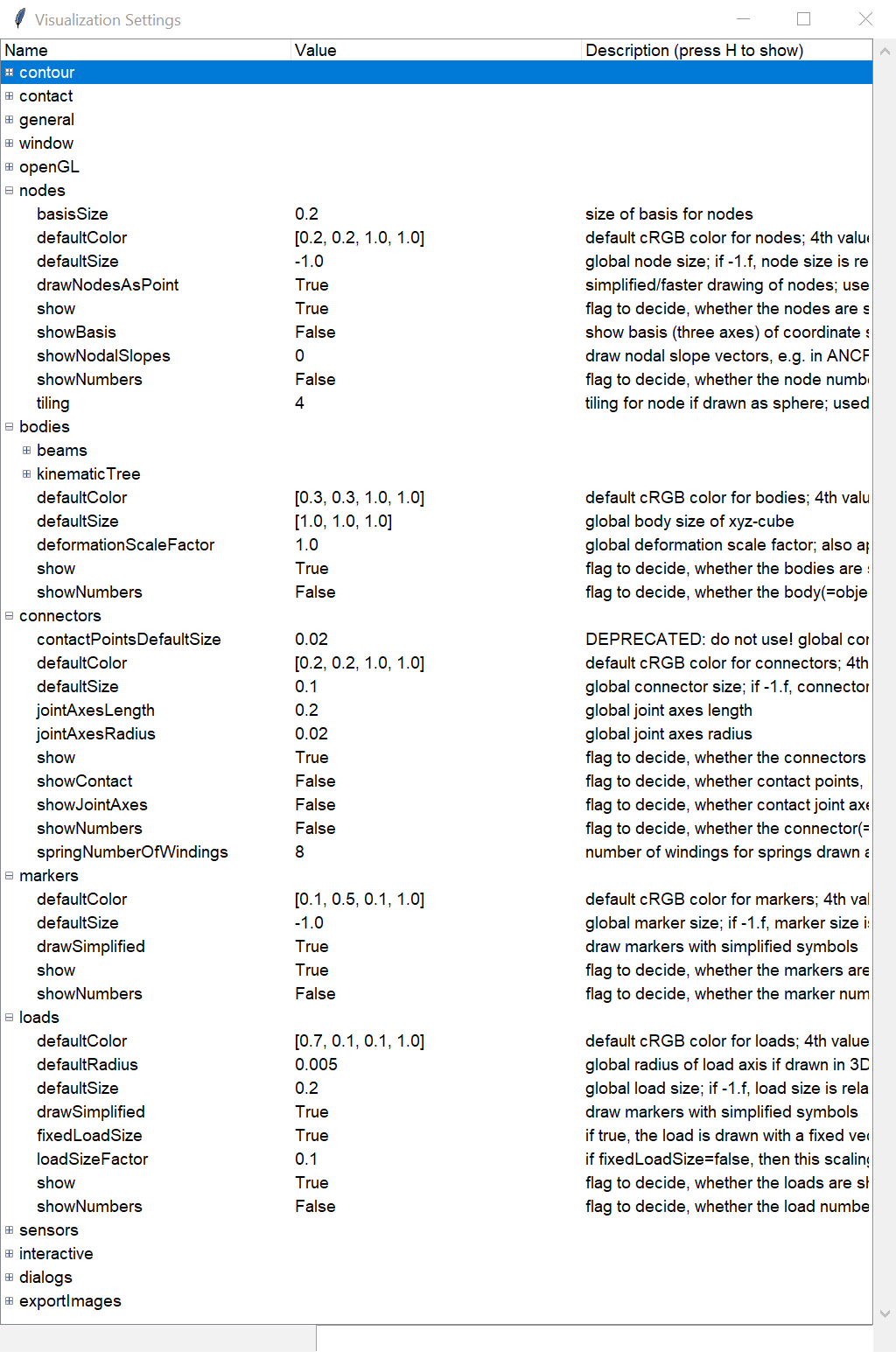

The visualization settings dialog is shown exemplarily in Fig. 5.

Note that this dialog is automatically created and uses Python’s tkinter, which is lightweight, but not very well suited if display scalings are large (e.g., on high resolution laptop screens). If working with Spyder, it is recommended to restart Spyder, if display scaling is changed, in order to adjust scaling not only for Spyder but also for Exudyn.

The appearance of visualization settings dialogs may be adjusted by directly modifying exudyn.GUI variables (this may change in the future). For example write in your code before opening the render window(treeEdit and treeview both mean the settings dialog currently used for visualization settings and partially for right-mouse-click):

import exudyn.GUI

exudyn.GUI.dialogDefaultWidth #unscaled width of, e.g., right-mouse-button dialog

exudyn.GUI.treeEditDefaultWidth = 800

exudyn.GUI.treeEditDefaultHeight = 600

exudyn.GUI.treeEditMaxInitialHeight = 600 #otherwise height is increased for larger screens

exudyn.GUI.treeEditOpenItems = ['general','contact'] #these tree items are opened each time the dialog is opened

#

exudyn.GUI.treeviewDefaultFontSize #this is the base font size of the dialog (also right-mouse-button dialog)

exudyn.GUI.useRenderWindowDisplayScaling #if True, the scaling will follow the current scaling of the render window; if False, it will use the \ ``tkinter``\ internal scaling, which uses the main screen where the dialog is created (which won't scale well, if the window is moved to another screen).

#

exudyn.GUI.textHeightFactor = 1.45 #this factor is used to increase height of lines in tree view as compared to font size

Fig. 5 View of visualization settings

Note: Press ‘V’ in render window to open dialog.

The visualization settings structure can be accessed in the system container SC (access per reference, no copying!), accessing every value or structure directly, e.g.,

SC.visualizationSettings.nodes.defaultSize = 0.001 #draw nodes very small

#change openGL parameters; current values can be obtained from SC.renderer.GetState()

#change zoom factor:

SC.visualizationSettings.openGL.initialZoom = 0.2

#set the center point of the scene (can be attached to moving object):

SC.visualizationSettings.openGL.initialCenterPoint = [0.192, -0.0039,-0.075]

#turn of auto-fit:

SC.visualizationSettings.general.autoFitScene = False

#change smoothness of a cylinder:

SC.visualizationSettings.general.cylinderTiling = 100

#make round objects flat:

SC.visualizationSettings.openGL.shadeModelSmooth = False

#turn on coloured plot, using y-component of displacements:

SC.visualizationSettings.contour.outputVariable = exu.OutputVariableType.Displacement

SC.visualizationSettings.contour.outputVariableComponent = 1 #0=x, 1=y, 2=z

Execute Command and Help

In addition to the Visualization settings dialog, a simple help window opens upon pressing key ‘H’.

It is also possible to execute single Python commands during simulation by pressing ‘X’, which opens a dialog, saying ‘Exudyn Command Window’.

Note that the dialog may appear behind the visualization window!

This dialog may be very helpful in long running computations or in case that you may evaluate variables for debugging.

The Python commands are evaluated in the global python scope, meaning that mbs or other variables of your scripts are available.

User errors are caught by exceptions, but in severe cases this may lead to crash.

To print values, always use print(...) to see the string representation of an object.

Useful examples (single lines) may be:

x=5 #or change any other variable used in Python user functions

print(mbs) #print current mbs overview

print(mbs.GetSensorValues(0))

#adjust simulation end time, in long-run simulations:

mbs.sys['dynamicSolver'].it.endTime = 1

#adjust output behavior

mbs.sys['dynamicSolver'].output.verboseMode = 0

You can also do quite fancy things during simulation, e.g., to deactivate joints (of course this may result in strange behavior):

n=mbs.systemData.NumberOfObjects()

for i in range(n):

d = mbs.GetObject(i)

#if 'Joint' in d['objectType']:

if 'activeConnector' in d:

mbs.SetObjectParameter(i, 'activeConnector', False)

Note that you could also change visualizationSettings in this way, but the Visualization settings dialog is much more convenient.

Changing simulationSettings within the execute command is dangerous and must be treated with care.

Some parameters, such as simulationSettings.timeIntegration.endTime are copied into the internal solver’s mbs.sys['dynamicSolver'].it structure.

Thus, changing simulationSettings.timeIntegration.endTime has no effect during simulation.

As a rule of thumb, all variables that are not stored inside the solvers structures may be adjusted by the simulationSettings passed to the solver (which are then not copied internally); see the C++ code for details. However, behavior may change in future and unexpected behavior or and changing simulationSettings will likely cause crashes if you do not know exactly the behavior, e.g., changing output format from text to binary … !

Specifically, newton and discontinuous settings cannot be changed on the fly as they are copied internally.

Graphics pipeline

There are basically two loops during simulation, which feed the graphics pipeline. The solver runs a loop:

compute step (or set up initial values)

finish computation step; results are in current state

copy current state to visualization state (thread safe)

signal graphics pipeline that new visualization data is available

the renderer may update the visualization depending on

graphicsUpdateIntervalinvisualizationSettings.general

The openGL graphics thread (=separate thread) runs the following loop:

render openGL scene with a given graphicsData structure (containing lines, faces, text, …)

go idle for some milliseconds

check if openGL rendering needs an update (e.g. due to user interaction) \(\ra\) if update is needed, the visualization of all items is updated – stored in a graphicsData structure)

check if new visualization data is available and the time since last update is larger than a presribed value, the graphicsData structure is updated with the new visualization state

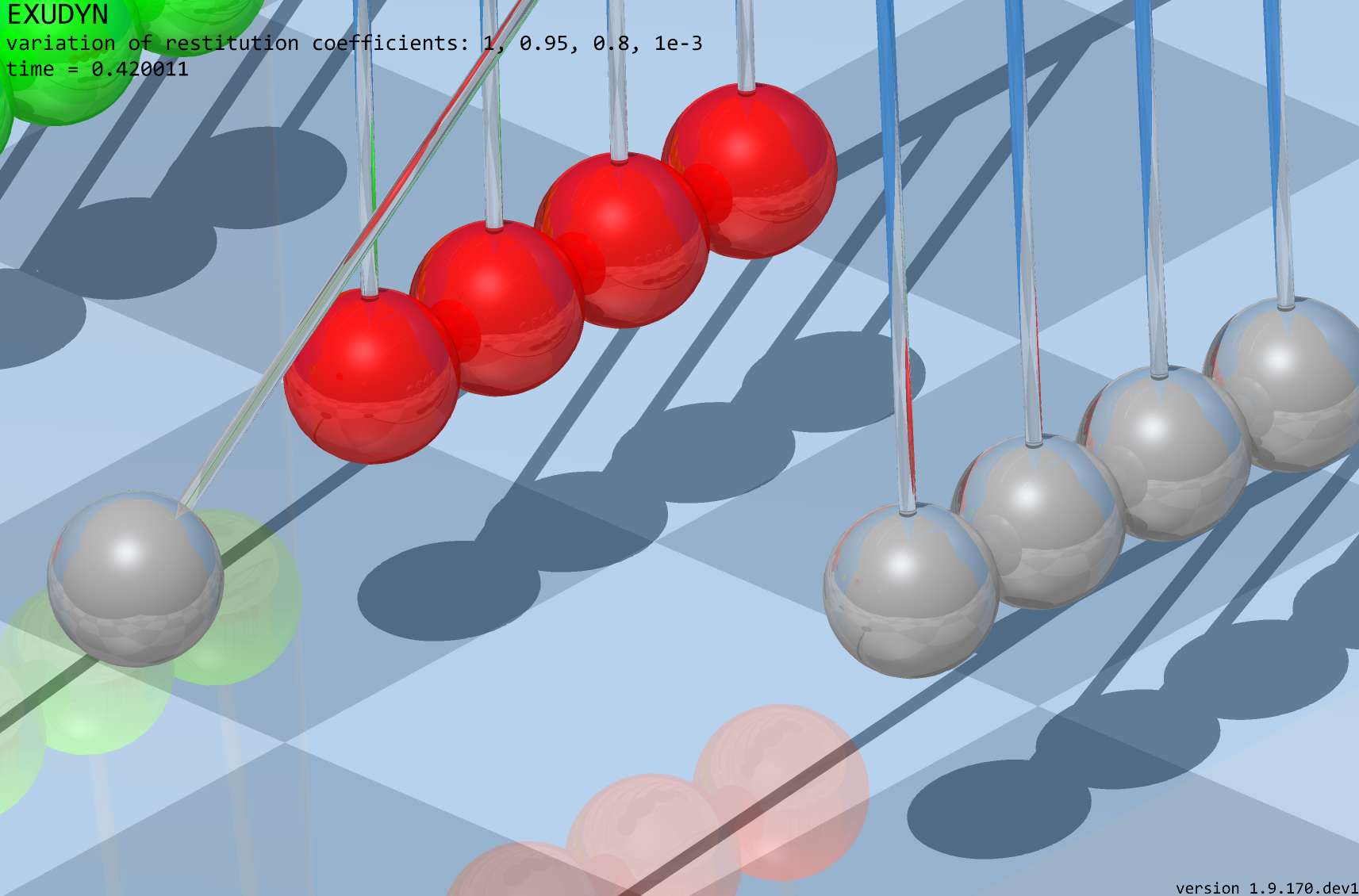

Raytracing

In order to compensate the limited functionality (but high compatibility) of OpenGL 1.3, an option for CPU-based software rendering (raytracing) has been added. This allows to include shadows and transparency correctly, with additional support for relections, refraction, emission, fog and materials. In the future, textures may be added as well.

Fig. 6 Example image of raytraced renderer view.

The basic things to know are:

Raytracing settings are collected in

SC.visualizationSettings.raytracer(in the following, we omit ‘SC.visualizationSettings’).Raytracing is activated by setting

raytracer.enable=True. Please make sure that you start with small render window sizes / complexity first.The render window size is adjusted by

window.renderWindowSize. Be careful with this settings.Adjust the

raytracer.numberOfThreadsfor optimal performance, useraytracer.verboseto see render times for different settings. For testing, useraytracer.imageSizeFactor>1to decrease the raytracer’s resolution (with same image size), whileopenGL.multiSamplingwill increase the resolution (anti-aliasing). Note that switching fromopenGL.multiSampling=1andraytracer.imageSizeFactor=4toopenGL.multiSampling=3andraytracer.imageSizeFactor=1increases computational costs by a factor \(4\times 4\times 3\times 3 = 144\). Use only one light, if sufficient (setopenGL.enableLight1=False).Scene, lights, shadow, clipping plane, etc. settings are taken form OpenGL settings and directly used in the software renderer, like

openGL.light0position,openGL.shadow,openGL.perspective,openGL.clippingPlaneNormal,openGL.showLines, etc.;some settings are in general, like

general.backgroundColororgeneral.drawWorldBasis;In order to see the advantages of the software renderer, materials have to be used, see below.

Materials:

Materials have the type

VSettingsMaterial, see description in Section VSettingsMaterial, for adjusting color, reflectivity, shininess, alpha-transparency, etc.;Materials can only be used within triangulated geometries (GraphicsData

TriangleList) using a material-flag in the color, likegraphics.Sphere(..., color=graphics.material.chrome). In the RGBA color, the alpha-channel is replaced by a material index which starts at 1000 (where 1000 represents material index 0). Note that in the regular OpenGL-rendering, alpha\(>\)1 is equivalent to alpha\(=\)1. The first 10 materials are linked toraytracer.material0 ... raytracer.material9.The material’s

baseColoris used if the color red-channel is set to \(-1\). Note that this allows to globally change the color of objects by changingbaseColorin the material settings invisualizationSettings. Summarizing, usingcolor=[1,0,0,graphics.material.indexSteel]chooses red color with steel material settings, whilecolor=[-1,-1,-1,graphics.material.indexSteel]will use the color of steel (but will be black for OpenGL renderer), identical withcolor=graphics.material.steel.The setting

backgroundColorReflectionscan be used to represent the background which is used for rendering, while the background is independently set to black or white. Otherwise, black background leads to black regions on highly reflective objects or very light regions for white backgrounds.System text messages (solver, version, etc.) are overlayed over raytracing and can be turned off using the settings in

general.showComputationInfoand similar. However, note that item texts are currently not shown in raytracer, affecting node numbers, etc.!

Limitations and risks:

Raytracing is CPU-based and therefore slow. Do not use very high resolution (4K) together with multisampling \(>1\). Start with small render window sizes (e.g. 600 \(\times\) 400)

Raytracing usually uses multithreading with speedups \(>10\) on 16 cores. However, this cannot be combined with multithreaded simulations. It is therefore recommended to use raytracing in the solution viewer, not during simulation.

If software rendering of a single frame gets to long (>4 seconds), timeouts become active and it may occasionally not work. There are some options to compensate, see above.

In general, it is recommended to start with default settings and experiment with changes using the visualization settings dialog.

To add raytracing to your project, do like this:

...

#sphere with chrome

graphics.Sphere(radius=radius,

color=graphics.color.dodgerblue[0:3]+[graphics.material.indexChrome],

nTiles=32)

ground = mbs.CreateGround(referencePosition=[0,0,0],

graphicsDataList=[gSphere])

#add mbs components

#assemble

#solve

...

#after computation, switch to raytracing

SC.visualizationSettings.openGL.multiSampling = 1

#SC.visualizationSettings.openGL.imageSizeFactor = 4 #reduce resolution for first tests!

SC.visualizationSettings.openGL.enableLight1 = False

SC.visualizationSettings.raytracer.numberOfThreads = 16 #adjust to your n-threads

SC.visualizationSettings.raytracer.enable = True

mbs.SolutionViewer()

Have fun!

Storing the model view

There is a simple way to store the current view (zoom, centerpoint, orientation, etc.) by using SC.renderer.GetState() and SC.renderer.SetState(),

see also Section Render state.

A simple way is to reload the stored render state (model view) after simulating your model once at the end of the simulation(

note that visualizationSettings.general.autoFitScene should be set False if you want to use the stored zoom factor):

import exudyn as exu

SC=exu.SystemContainer()

SC.visualizationSettings.general.autoFitScene = False #prevent from autozoom

SC.renderer.Start()

if 'renderState' in exu.sys:

SC.renderer.SetState(exu.sys['renderState'])

#+++++++++++++++

#do simulation here and adjust model view settings with mouse

#+++++++++++++++

#store model view for next run:

SC.renderer.Stop() #stores render state in exu.sys['renderState']

Alternatively, you can obtain the current model view from the console after a simulation, e.g.,

In[1] : SC.renderer.GetState()

Out[1]:

{'centerPoint': [1.0, 0.0, 0.0],

'maxSceneSize': 2.0,

'zoom': 1.0,

'currentWindowSize': [1024, 768],

'modelRotation': [[ 0.34202015, 0. , 0.9396926 ],

[-0.60402274, 0.76604444, 0.21984631],

[-0.7198463 , -0.6427876 , 0.26200265]])}

which contains the last state of the renderer.

Now copy the output and set this with SC.renderer.SetState in your Python code to have a fixed model view in every simulation (SC.renderer.SetState AFTER SC.renderer.Start()):

SC.visualizationSettings.general.autoFitScene = False #prevent from autozoom

SC.renderer.Start()

renderState={'centerPoint': [1.0, 0.0, 0.0],

'maxSceneSize': 2.0,

'zoom': 1.0,

'currentWindowSize': [1024, 768],

'modelRotation': [[ 0.34202015, 0. , 0.9396926 ],

[-0.60402274, 0.76604444, 0.21984631],

[-0.7198463 , -0.6427876 , 0.26200265]])

SC.renderer.SetState(renderState)

#.... further code for simulation here

Note that in the current version of Exudyn there is more data stored in render state, which is not used in SC.renderer.SetState,

see also Section Render state.

Graphics user functions via Python

There are some user functions in order to customize drawing:

You can assign graphicsData to the visualization to most bodies, such as rigid bodies in order to change the shape. Graphics can also be imported from files (

exu.graphics.FromSTLfileASCII,exu.graphics.FromSTLfile, ) using the established format STL(STereoLithography or Standard Triangle Language; file format available in nearly all CAD systems).Some objects, e.g.,

ObjectGenericODE2orObjectRigidBody, provide customized a functiongraphicsDataUserFunction. This user function just returns a list of GraphicsData, see Section GraphicsData. With this function you can change the shape of the body in every step of the computation.Specifically, the

graphicsDataUserFunctioninObjectGroundcan be used to draw any moving background in the scene.

Note that all kinds of graphicsDataUserFunctions need to be called from the main (=computation) process as Python functions may not be called from separate threads (GIL). Therefore, the computation thread is interrupted to execute the graphicsDataUserFunction between two time steps, such that the graphics Python user function can be executed. There is a timeout variable for this interruption of the computation with a warning if scenes get too complicated.

Color, RGBA and alpha-transparency

Many functions and objects include color information. In order to allow alpha-transparency, all colors contain a list of 4 RGBA values, all values being in the range [0..1]:

red (R) channel

green (G) channel

blue (B) channel

alpha (A) value, representing the so-called alpha-transparency (A=0: fully transparent, A=1: solid)

E.g., red color with no transparency is obtained by the color=[1,0,0,1].

Color predefinitions are found in graphics.py, e.g., using graphics.color.red or graphics.color.steelblue as well a list of 16 colors graphics.colorList, which is convenient to be used in a loop creating objects.

Earlier, special colors were given in exudyn.graphicsDataUtilities.py, e.g., color4red or color4steelblue as well as color4list, which are marked as deprecated.

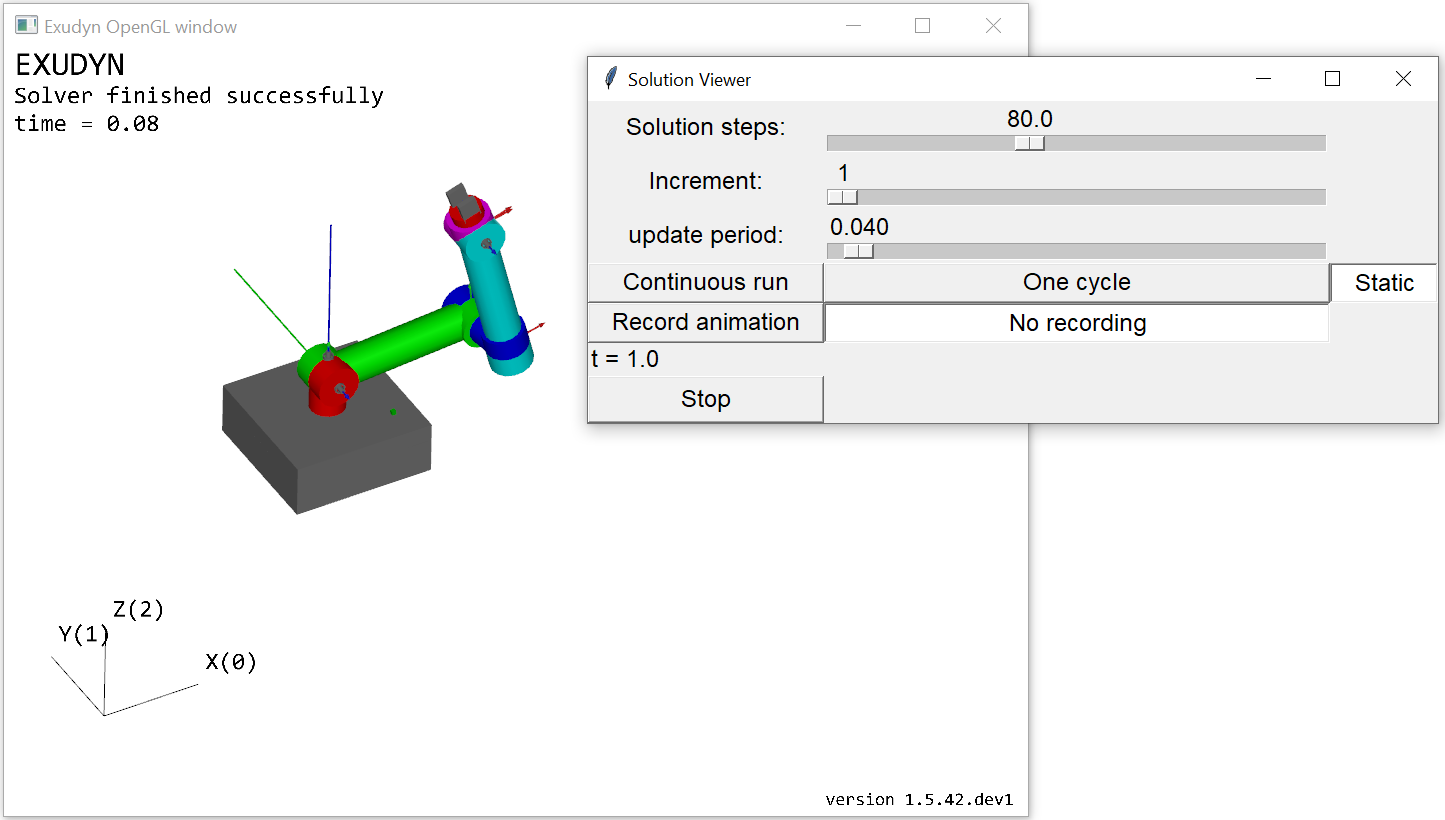

Solution viewer

Exudyn offers a convenient WYSIWYS – ‘What you See is What you Simulate’ interface, showing you the computation results during simulation in the render window. If you are running large models, it may be more convenient to watch results after simulation has been finished. For this, you can use

interactive.SolutionViewer, see Sectioninteractive.AnimateModes, lets you view the animation of computed modes, see Section

shown exemplary in Fig. 7.

Fig. 7 View of SolutionViewer (as of Exudyn 1.5.42.dev1)

The SolutionViewer adds a tkinter interactive dialog, which lets you interact with the model, with the following features:

The SolutionViewer represents a ‘Player’ for the dynamic solution or a series of static solutions, which is available after simulation if

solutionSettings.writeSolutionToFile = TrueThe parameter

solutionSettings.solutionWritePeriodrepresents the time period used to store solutions during dynamic computations.As soon as ‘Run’ is pressed, the player runs (and it may be started automatically as well)

In the ‘Static’ mode, drag the slider ‘Solution steps’ to view the solution steps

In the ‘Continuous run’ mode, the player runs in an infinite loop

In the ‘One cycle’ mode, the player runs from the current position to the end; this is perfectly suited to record series of images for creating animations, see Section Generating animations and works together with the visualization settings dialog.

In the ‘Record animation’ mode, the player records frames that are shown in the render window; before pressing on ‘Record animation’, press ‘Stop’ and switch to ‘One cycle’. Then put the solution steps slider to the first frame and press ‘Record animation’, which stores images in the current subfolder ‘images’ as ‘frame00001.png’ with increasing number, using PNG by default. The number is increased and can only be reset after new start of SolutionViewer.

Since Exudyn V1.9.83, the button ‘Make mp4’ allows to directly generate animation files, see next section.

The solution should be loaded with

LoadSolutionFile('coordinatesSolution.txt'), where ‘coordinatesSolution.txt’ represents the stored solution file,

see

exu.SimulationSettings().solutionSettings.coordinatesSolutionFileName

You can call the SolutionViewer either in the model, or at the command line / IPython to load a previous solution (belonging to the same mbs underlying the solution!):

from exudyn.utilities import LoadSolutionFile

sol = LoadSolutionFile('coordinatesSolution.txt')

mbs.SolutionViewer(solution=sol)

By default and as a recommended way, if no solution is provided, SolutionViewer tries to reload the solution of the previous simulation that is referred to from mbs.sys['simulationSettings']:

#... mbs has been previously solved

mbs.SolutionViewer()

An example for the SolutionViewer is integrated into the Examples/ directory, see solutionViewerTest.py.

Generating animations

In many dynamics simulations, it is very helpful to create animations in order to better understand the motion of bodies. Specifically, the animation can be used to visualize the model much slower or faster than the model is computed.

Animations are created based on a series of images (frames, snapshots) taken during simulation. It is important, that the current view is used to record these images – this means that the view should not be changed during the recording of images. The easiest way to create animations, is using the SolutionViewer with its integrated features, see Section Solution viewer.

To turn on recording of images during solving, set the following flag to a positive value

simulationSettings.solutionSettings.recordImagesInterval = 0.01

which means, that after every 0.01 seconds of simulation time, an image of the current view is taken and stored in the directory and filename (without filename ending) specified by

SC.visualizationSettings.exportImages.saveImageFileName = "myFolder/frame"

By default, a consecutive numbering is generated for the image, e.g., ‘frame0000.png, frame0001.png,…’. Note that the standard file format PNG with ending ‘.png’ uses compression libraries included in glfw, while the alternative TGA format produces ‘.tga’ files which contain raw image data and therefore can become very large.

To create animation files, an external tool FFMPEG is used to efficiently convert a series of images into an animation. Since Exudyn V1.9.83, ffmpeg is integrated into the solution viewer (button ‘Make mp4’), which requires prior installation using pip install ffmpeg-python .

Note that you may also need to install ffmpeg itself, depending on your platform.

\(\ra\) see theDoc.pdf !

Examples, test models and test suite

The main collection of examples and models is available under

main/pythonDev/Examplesmain/pythonDev/TestModels

You can use these examples to build up your own realistic models of multibody systems. Very often, these models show the way which already works. Alternative ways may exist, but sometimes there are limitations in the underlying C++ code, such that they won’t work as you expect.

We would like to note that, even that some examples and test models contain comparison to papers of the literature or analytical solutions, there are many models which may not contain real mechanical values and these models may not be converged in space or time (in order to keep running our test suite in less than a minute).

Finally, note that the main/pythonDev/TestModels are often only intended to preserve functionality

in the Python and C++ code (e.g., if global methods are changed), but they should not be misinterpreted as validation of the

implemented methods. The TestModels are used in the Exudyn TestSuite TestModels/runTestSuite.pywhich is run after a full build of Python versions. Output for very version is written

to main/pythonDev/TestSuiteLogs containing the Exudyn version and Python version. At the end of these

files, a summary is included to show if all models completed successfully (which means that a certain error level is achieved, which is rather small and different for the models).

There are also performance tests (e.g., if a certain implementation leads to a significant drop of performance).

However, the output of the performance tests is not stored on github.

We are trying hard to achieve error-free algorithms of physically correct models, but there may always be some errors in the code.

Removing convergence problems and solver failures

Nonlinear formulations (such as most multibody systems, especially nonlinear finite elements) cause problems and there is no general nonlinear solver which may reliably and accurately solve such problems. Tuning solver parameters is at hand of the user. In general, the Newton solver tries to reduce the error by the factor given in

simulationSettings.staticSolver.newton.relativeTolerance(for static solver),

which is not possible for very small (or zero) initial residuals. The absolute tolerance is helping out as a lower bound for the error, given in

simulationSettings.staticSolver.newton.absoluteTolerance(for static solver),

which is by default rather low (1e-10) – in order to achieve accurate results for small systems or small motion (in mm or \(\mu\)m regime). Increasing this value helps to solve such problems. Nevertheless, you should usually set tolerances as low as possible because otherwise, your solution may become inaccurate.

The following hints / rules for described problems shall be followed.

static solver: load steps get very small even if the solution seems to be smooth (or linear) and less steps are expected:

→ this may happen for system without loads; larger number of steps may happen for finer discretization;→ you may adjust (increase).newton.relativeTolerance/.newton.absoluteTolerancein static solver or in time integration to resolve such problems, but check if solution achieves according accuracystatic solver: load steps are reduced significantly for highly nonlinear problems:

→ solver repeatedly writes that steps are reduced \(\ra\) try to useloadStepGeometricand use a largeloadStepGeometricRange: this allows to start with very small loads in which the system is nearly linear (e.g. for thin strings or belts under gravity).static solver: system is (nearly) kinematic:

→ a static solution can be achieved usingstabilizerODE2term, which adds mass-proportional stiffness terms during load steps \(< 1\); see also hints for singular Jacobians belowvery small loads or even zero loads do not converge:

SolveDynamicorSolveStaticterminated due to errors→ the reason is the nonlinearity of formulations (nonlinear kinematics, nonlinear beam, etc.) and round off errors, which restrict Newton to achieve desired tolerances→ adjust (increase).newton.relativeTolerance/.newton.absoluteTolerancein static solver or in time integration→ in many cases, especially for static problems, the.newton.newtonResidualMode = 1evaluates the increments; the nonlinear problems is assumed to be converged, if increments are within given absolute/relative tolerances; this also works usually better for kinematic solutionsfor discontinuous problems:

→ try to adjust solver parameters; especially thediscontinuous.iterationToleranceanddiscontinuous.maxIterations; try to make smaller load or time steps in order to resolve switching points of contact or friction; generalized alpha solvers may cause troubles when reducing step sizes \(\ra\) use TrapezoidalIndex2 solver→ in case of user functions, make sure that there is no switching inside the user function (if orsignfunction); switching must be done in the PostNewtonStep, otherwise convergence severely sufferssingular Jacobians or redundant constraints:

→ in case of systems that lead to a singular Jacobian due to redundant constraints or kinematic DOF in static solutions, you may switch to Eigen’s FullPivotLU solver using:→simulationSettings.linearSolverType = exu.LinearSolverType.EigenDenseand→simulationSettings.linearSolverSettings.ignoreSingularJacobian=True;→ however, check your results as they may be erroneous, because the solver tries to find an optimal solution / compromise which may not be what you intend to get!if you see further problems, please post them (including relevant example) at the Exudyn github page!

Performance and ways to speed up computations

Multibody dynamics simulation should be accurate and reliable on the one hand side. Most solver settings are such that they lead to comparatively reliable results. However, in some cases there is a significant possibility for speeding up computations, which are described in the following list. Not all recommendations may apply to your models.

The following examples refer to simulationSettings = exu.SimulationSettings().

In general, to see where CPU time is lost, use the option turn on simulationSettings.displayComputationTime = True to see which parts of the solver need most of the time (deactivated in exudynFast versions!).

In addition to Exudyn’s internal time measurements, in Spyder (or IPython) you can use magic commands such as \%timeit -n10 mbs.SolveDynamic() to evaluate the time spent for a specific command with number of repetitions given after -n. This may be particularly interesting in Python user functions to see where time is lost.

To activate the Exudyn C++ versions without range checks, which may be approx. 30 percent faster in some situations, use the following code snippet before first import of exudyn:

import sys

sys.exudynFast = True #this variable is used to signal to load the fast exudyn module

import exudyn as exu

The faster versions are available for all release versions, but only for some .dev1 development versions (Python 3.10), which can be determined by trying import exudyn.exudynCPPfast.

However, there are many ways to speed up Exudyn in general:

for models with more than 50 coordinates, switching to sparse solvers might greatly improve speed:

simulationSettings.linearSolverType = exu.LinearSolverType.EigenSparsewhen preferring dense direct solvers, switching to Eigen’s PartialPivLU solver might greatly improve speed:

simulationSettings.linearSolverType = exu.LinearSolverType.EigenDense; however, the flagsimulationSettings.linearSolverSettings.ignoreSingularJacobian=Truewill switch to the much slower (but more robust) Eigen’s FullPivLUtry to avoid Python functions or try to speed up Python functions; if this is not possible, see solutions below

instead of user functions in objects or loads (computed in every iteration), some problems would also work if these parameters are only updated in

mbs.SetPreStepUserFunction(...)Python user functions can be speed up (since Exudyn V1.7.40) by converting conventional Python functions into Exudyn (internal) symbolic user functions, which have similar performance as C++ functions with the ability to parallelize; see Section Symbolic

Alternatively, Python user functions can be speed up using the Python numba package, using

@jitin front of functions (for more options, see https://numba.pydata.org/numba-doc/dev/user/index.html); Example given inExamples/springDamperUserFunctionNumbaJIT.pyshowing speedups of factor 4; more complicated Python functions may see speedups of 10 - 50for discontinuous problems, try to adjust solver parameters; especially the discontinuous.iterationTolerance which may be too tight and cause many iterations; iterations may be limited by discontinuous.maxIterations, which at larger values solely multiplies the computation time with a factor if all iterations are performed

For multiple computations / multiple runs of Exudyn (parameter variation, optimization, compute sensitivities), you can use the processing sub module of Exudyn to parallelize computations and achieve speedups proporional to the number of cores/threads of your computer; specifically using the

multiThreadingoption or even using a cluster (usingdispy, seeParameterVariation(...)function)In case of multiprocessing and cluster computing, you may see a very high CPU usage of “Antimalware Service Executable”, which is the Microsoft Defender Antivirus; you can turn off such problems by excluding

python.exefrom the defender (on your own risk!) in your settings:

Settings \(\ra\) Update & Security \(\ra\) Windows Security \(\ra\) Virus & threat protection settings \(\ra\) Manage settings \(\ra\) Exclusions \(\ra\) Add or remove exclusions

Possible speed ups for dynamic simulations:

for implicit integration, turn on modified Newton, which updates jacobians only if needed:

simulationSettings.timeIntegration.newton.useModifiedNewton = Trueuse multi-threading:

simulationSettings.parallel.numberOfThreads = ..., depending on the number of cores (larger values usually do not help); improves greatly for contact problems, but also for some objects computed in parallel; will improve significantly in futuredecrease number of steps (

simulationSettings.timeIntegration.numberOfSteps = int(tEnd/h)) by increasing the step size \(h\) if not needed for accuracy reasons; not that in general, the solver will reduce steps in case of divergence, but not for accuracy reasons, which may still lead to divergence if step sizes are too largeswitch off measuring computation time, if not needed:

simulationSettings.displayComputationTime = Falsetry to switch to explicit solvers, if problem has no constraints and if problem is not stiff

try to have constant mass matrices (see according objects, which have constant mass matrices; e.g. rigid bodies using RotationVector Lie group node have constant mass matrix)

for explicit integration, set

computeEndOfStepAccelerations = False, if you do not need accurate evaluation of accelerations at end of time step (will then be taken from beginning)for explicit integration, set

explicitIntegration.computeMassMatrixInversePerBody=True, which avoids factorization and back substitution, which may speed up computations with many bodies / particlesif you are sure that your mass matrix is constant, set:

simulationSettings.timeIntegration.reuseConstantMassMatrix = True; check results!check that

simulationSettings.timeIntegration.simulateInRealtime = False; if set True, it breaks down simulation to real timedo not record images, if not needed:

simulationSettings.solutionSettings.recordImagesInterval = -1in case of bad convergence, decreasing the step size might also help; check also other flags for adaptive step size and for Newton

use

simulationSettings.timeIntegration.verboseMode = 1; larger values create lots of output which drastically slows downuse

simulationSettings.timeIntegration.verboseModeFile = 0, otherwise output written to fileadjust

simulationSettings.solutionSettings.sensorsWritePeriodto avoid time spent on writing sensor filesuse

simulationSettings.timeIntegration.writeSolutionToFile = False, otherwise much output may be written to file;if solution file is needed, adjust

simulationSettings.solutionSettings.solutionWritePeriodto larger values and also adjustsimulationSettings.solutionSettings.outputPrecision, e.g., to 6, in order to avoid larger files; also adjustsimulationSettings.solutionSettings.exportVelocities = FalseandsimulationSettings.solutionSettings.exportAccelerations = Falseto avoid large output files